California's drought linked to greenhouse gases, climate change in Stanford study

By Lisa M. Kriegerlkrieger@mercurynews.com

POSTED: 09/29/2014

By Lisa M. Kriegerlkrieger@mercurynews.com

POSTED: 09/29/2014

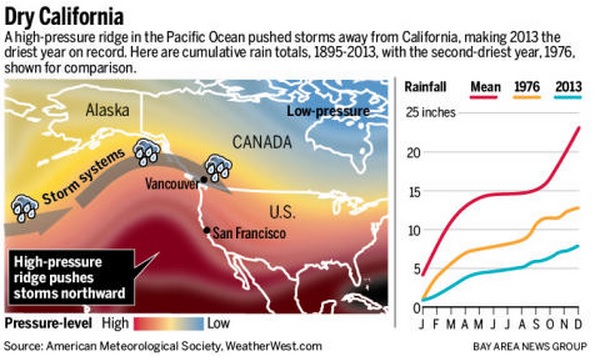

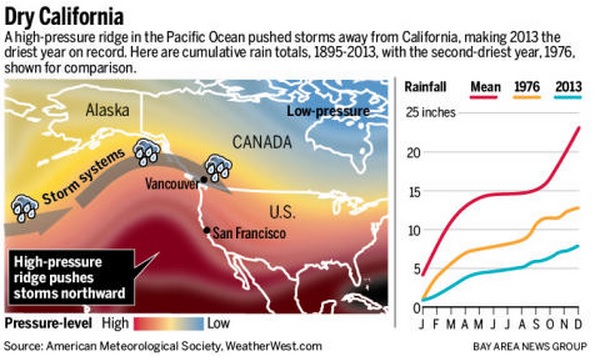

The stubborn high-pressure systems that block California rains are linked to the abundance of human-caused greenhouse gases that heat the oceans, according to a major paper released Monday by Stanford scientists.

But two other new studies disagree -- saying there's no evidence that warming ocean waters are to blame for our drought.

The dispute comes at the end of the state's official "water year," which closes Tuesday with less than 60 percent of average precipitation. California's major reservoirs are collectively holding just one-third of their capacity.

The three teams of scientists contributing to an annual analysis of extreme weather events agree that there is a region of exceptionally high, record-breaking ocean temperatures in the North Pacific, nicknamed "The Blob." It's big enough to cover the United States 300 feet deep.

A Stanford study concludes California’s extraordinary drought is

linked to the abundance of greenhouse gases created by burning fossil fuels.

A Stanford study concludes California's extraordinary drought is linked to the

abundance of greenhouse gases created by burning fossil fuels. (Altaf Qadri/Associated

Press)

And they agree that warm Pacific waters -- which may be linked to persistent

high-pressure systems -- can trigger changes in how the atmosphere sweeps across

our landscape.

But did we inflict this devastating drought upon ourselves?

The evidence isn't there, conclude the editors of the report -- an anthology of more than 20 climate studies published in the Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society.

"The comparison of the three studies for the same extreme event, each using different methods and metrics, revealed sources of uncertainty," it asserts.

Leading off the three California reports, the Stanford team concluded that high-pressure systems like our current "Ridiculously Resilient Ridge," diverting storms away from California, are much more likely to form in the presence of concentrations of greenhouse gases, responsible for climate change.

Advertisement

"We find that it is very likely that global warming has tripled the probability

of this atmospheric configuration occurring," said Stanford climate scientist

Noah Diffenbaugh, associate professor of environmental earth system science,

who led the research.

High-pressure systems cause fewer storms to reach California, agreed a second team. But they can also increase atmospheric humidity, boosting the odds of flooding.

"These effects counteract each other, contributing to no appreciable long-term change in risk of dry climate extremes over California," according to a paper by Hailan Wang and Siegfried Schubert of NASA's Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Md.

A third team concluded that ocean warming, while real, is not contributing to our drought, because the blob of warming water is too far west of the critical region. But warming will stress our water availability, warned Daithi Stone of Lawrence Berkeley National Labs and two Santa Barbara-based scientists.

Increasing air temperatures "will impact the timing and availability of snowmelt, and amplify demand for water," the team wrote.

Human-caused global warming caused extreme weather elsewhere, according to the other studies in the annual report.

Specifically, it is blamed for lethal heat waves in Australia and Korea.

But natural variability plays a role in other lethal events, such as flooding and India and deep snow in the Spanish Pyrenees Mountains.

Accurately modeling rainfall in a complex landscape, especially a place like California, can be tricky.

The Stanford study does not explicitly blame California's drought on climate change. But it says there is a high statistical likelihood that the large-scale atmospheric conditions that fend off rainstorms occur more frequently now than in the climate before we emitted large amounts of greenhouse gases,

To test their theory, the Stanford team applied advanced statistical techniques to a large suite of climate model simulations. One set mirrored the present climate, in which the atmosphere is warming due to human emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases. In the other, greenhouse gases were kept at a level similar to those before the Industrial Revolution began in the early 18th century.

They found that the conditions associated with a formation of a ridge over the northeastern Pacific were at least three times as likely to occur in the present climate as in the preindustrial climate.

They also found that such extreme conditions are consistently tied to unusually low precipitation in California.

Contact Lisa M. Krieger at 650-492-4098.